A Handout for Educational Professionals.

A common misperception is that giving a student the “gift” of another year in the same grade will allow the child time to mature (academically and socially); however, grade retention has been associated with numerous deleterious outcomes. Without specific targeted interventions, most retained students do not “catch up.”

Research Regarding Retention:

Temporary gains. Research indicates that academic improvements may be observed during the year the student is retained, however, achievement gains typically decline within 2–3 years of retention.

Negative impact on achievement and adjustment. Research has shown that grade retention is associated with negative outcomes in all areas of student achievement (e.g., reading, math, oral and written language) and social and emotional adjustment (e.g., peer relationships, self-esteem, problem behaviors, and attendance).

Negative long-term effects. By adolescence, experiencing grade retention is associated with emotional distress, low self-esteem, poor peer relations, cigarette use, alcohol and drug abuse, early onset of sexual activity, suicidal intentions, and violent behaviors.

Retention and dropout. Students who have been retained are much more likely to drop out of school.

Consequences during adulthood. As adults, individuals who repeated a grade are more likely than adults who did not repeat a grade to be unemployed, living on public assistance, or in prison.

What can educational professionals do to help?

It is imperative that we implement effective strategies that enable at-risk students to succeed. Addressing problems early improves chances for success. Consider the following:

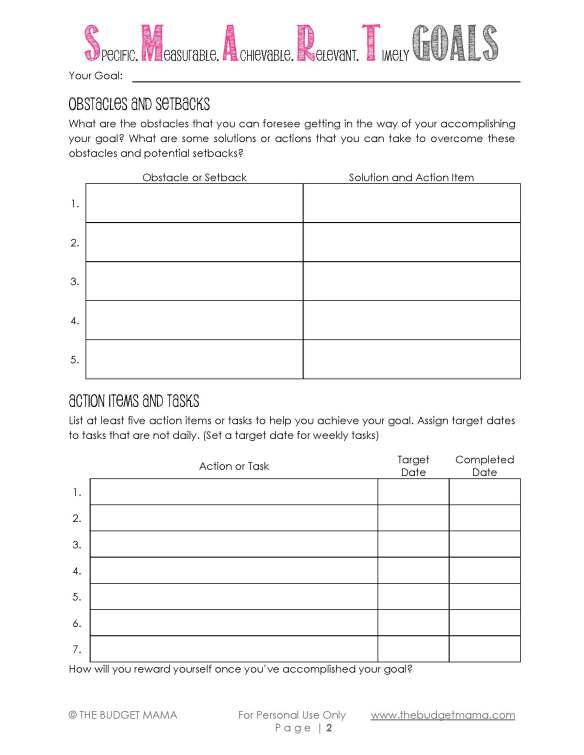

• Identify the unique strengths and needs of the student.

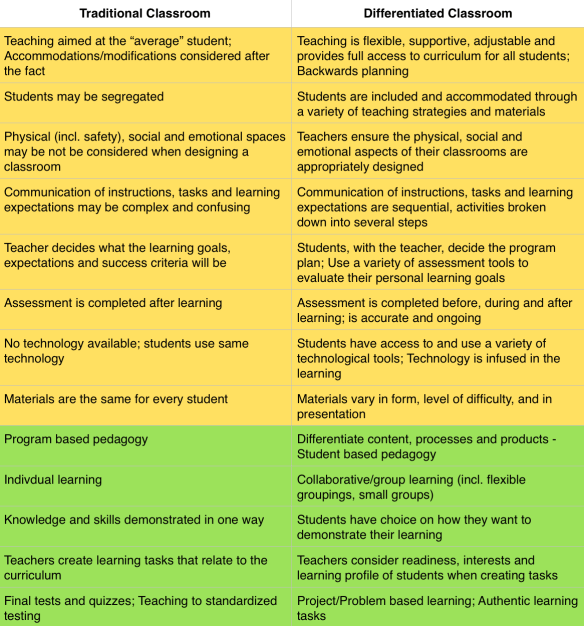

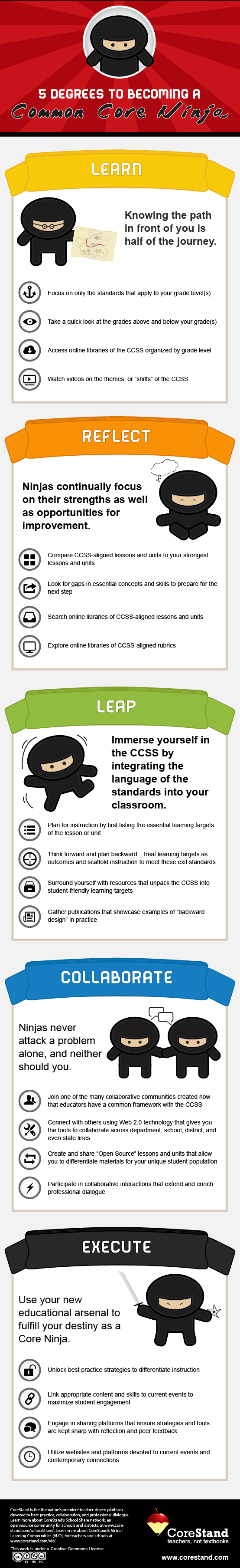

• Implement effective research-based teaching strategies (e.g., Preschool Programs, Access to School-Wide Evidence-Based Programs, Summer School and After School Programs, Looping and Multi-Aged Classrooms, School-Based Mental Health Programs, Parental Involvement, Early Reading Programs, Direct Instruction, Mnemonic Strategies, Curriculum Based Measurement, Cooperative Learning, Behavior and Cognitive Behavior Modification Strategies)

• Identify learning and behavior problems early to help avoid the cumulative effects of ongoing difficulties. • Discuss concerns and ideas with parents and other educational professionals at the school.

• Provide structured activities and guidance for parents or other adults to work with the child to help develop necessary skills.

• Collaborate with other professionals in a multidisciplinary student-support team.

This handout for educational professionals was adapted from a handout developed for teachers. Jimerson, S., Woehr, S., Kaufman, A., & Anderson, G. (2004). Grade retention and promotion: Important information for educators. In A.S. Canter, S.A. Carroll, L. Paige, & I. Romero (Eds.), Helping Children at Home and School: Handouts From Your School Psychologist (2nd ed., Section 3, pp. 61– 64). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Source