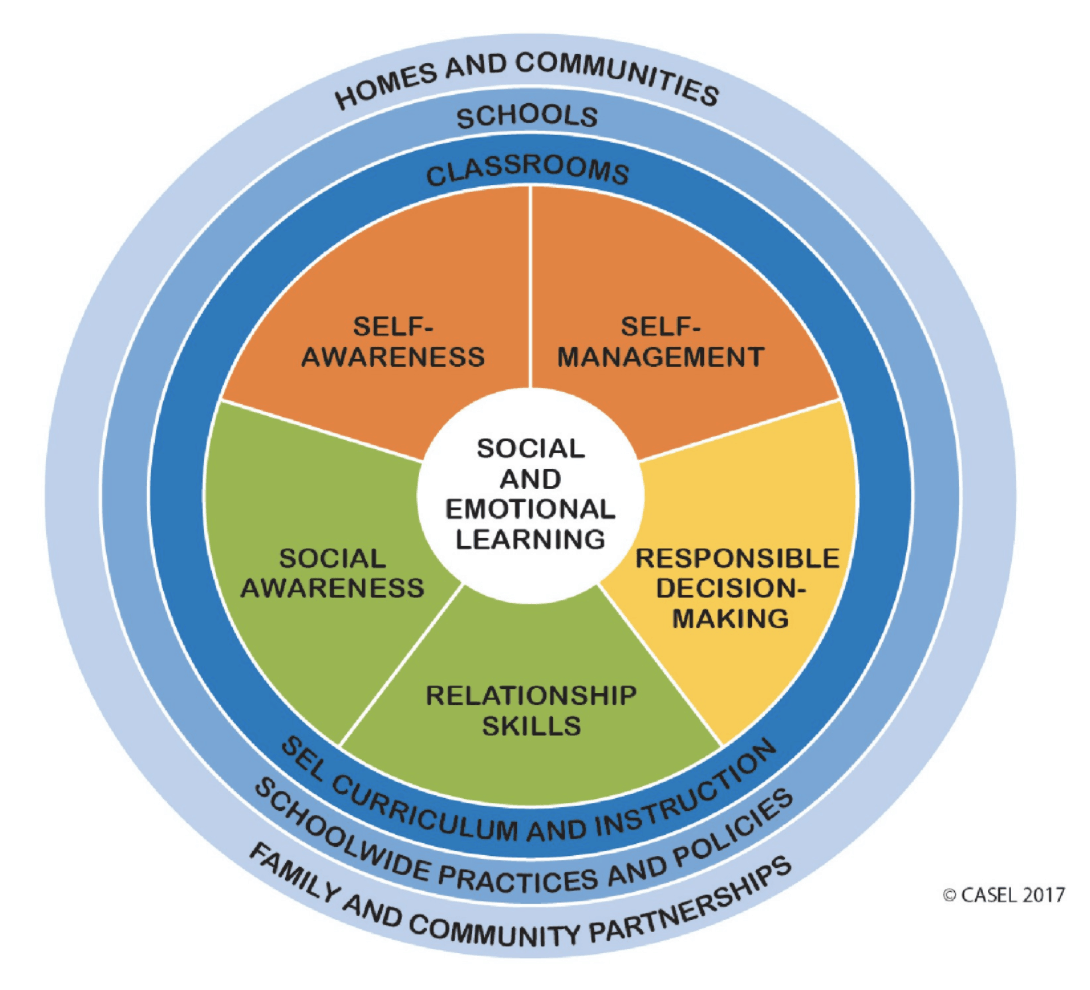

SEL is needed more than ever in schools. Here is some amazing resources and materials to help support teaching SEL skills in a very accessible manner. Take some time and look around the resources below.

SOURCE

Who created Be Good People?

Be Good People was a “quarantine project” developed between April and July 2020 by a team of educators who worked for or with the St. Croix River Education District (SCRED):

- Nic van Oss, School Psychologist by training

- Raycheal Zamora, School Psychologist and Special Education Teacher by training

- Molly Gavett, Board Certified Behavior Analyst by training

- Courtney Strelow, Special Education Teacher by training

- Ry Bostrom, Special Education Teacher by training

Be Good People was a reinvention and evolution of curriculum resources that Molly and Nic had created and used at the Chisago Lakes Education Center, a K-12 behavior-focused setting IV program. The aforementioned team “sprinted” to create Be Good People because it quickly became apparent that the COVID pandemic would have a significant mental health impact, and the team wanted to ensure that our schools were able to access and rapidly implement high-quality SEL instruction across all levels of the MTSS framework, particularly Tier 1.

Development of the curriculum is an ongoing process, which is led by SCRED’s SEL Services Team (Nic van Oss, Angela Christenson, and Kevin Krzenski) and Autism Services Coordinator (Raycheal Zamora).

Lessons and Extension Activities

Organized by Minnesota’s overall K-12 learning goals. Perfect for planning the scope and sequence of your intervention or for browsing.

Self-Awareness

Demonstrates an awareness and understanding of own emotions.

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Demonstrates awareness of personal strengths, challenges, aspirations, and cultural, linguistic, and community assets.

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Demonstrates awareness of personal rights and responsibilities.

- Showing Respect

- Accepting the Consequences of Your Actions

- Rewarding Yourself

- Advocating

- Respecting Others’ Belongings

- Borrowing Others’ Belongings

- Sharing Your Belongings

- Dealing with Boredom

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Self-Management

Demonstrates the skills to manage and express their emotions, thoughts, impulses, and stress in effective ways.

- Managing Stress

- Using Calming Strategies

- Coping with Sadness or Grief

- Expressing Your Feelings

- Expressing Pride

- Using Positive Self-Talk

- Developing Your Values and Beliefs

- Using a Growth Mindset

- Dealing with Mistakes or Disappointment

- Dealing with Embarrassment

- Dealing with Feeling Left Out

- Dealing with Rejection

- Dealing with Changes

- Showing Self-Control

- Being Patient

- Staying on Task

- Ignoring Distractions

- Organizing Tasks and Planning Ahead

- Studying for Quizzes and Tests

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Demonstrates the skills to set, monitor, adapt, achieve, and evaluate goals.

- Setting Goals

- Completing Assigned Tasks

- Completing Homework

- Accepting Feedback

- Gathering Information

- Seeking Professional Assistance

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Social Awareness

Demonstrates awareness of and empathy for individuals, their emotions, experiences, and perspectives through a cross-cultural lens.

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Demonstrates awareness and respect of groups and their cultures, languages, identities, traditions, values, and histories.

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Demonstrates awareness of how individuals and groups cooperate toward achieving common goals and ideals.

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Demonstrates awareness of external supports and when supports are needed.

- Asking Questions

- Asking for Help

- Asking for Clarification

- Accepting Help

- Responding to Teasing or Bullying

- Reporting Emergencies

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Relationship Skills

Demonstrates a range of communication and social skills to interact effectively.

- Using Active Listening

- Using an Appropriate Voice Volume and Tone

- Getting Another Person’s Attention

- Seeking Positive Attention

- Sharing Attention

- Taking Turns

- Encouraging Others

- Offering Feedback

- Giving Compliments

- Showing Gratitude

- Accepting Compliments

- Being Assertive

- Making a Complaint

- Preparing for Social Situations

- Participating in Group Discussions

- Showing Sportsmanship

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Cultivates constructive relationships with others.

- Greeting Others

- Starting a Conversation

- Having a Conversation

- Ending a Conversation

- Introducing Yourself

- Introducing Others

- Suggesting an Activity

- Choosing Good Friends

- Making New Friends

- Maintaining Relationships

- Participating in Group Activities

- Giving Instructions

- Responding to Pressure from Others

- Persuading Others

- Setting Appropriate Boundaries

- Showing Appropriate Affection

- Respecting Others’ Privacy

- Respecting Others’ Personal Information

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Identifies and demonstrates approaches to addressing interpersonal conflict.

- Preparing for a Difficult Conversation

- Responding to Conflict

- Responding to Complaints

- Negotiating

- Apologizing

- Accepting Apologies

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Responsible Decision Making

Considers ethical standards, social and community norms, and safety concerns in making decisions.

- Being on Time and Prepared

- Being Reliable

- Being an Appropriate Role Model

- Following Instructions

- Following Rules

- Using Appropriate Language

- Using Appropriate Humor

- Communicating Honestly

- Avoiding Trouble

- Responding to Others’ Inappropriate Behavior

- Reporting Inappropriate Behavior

- Getting the Teacher’s Attention

- Making a Request

- Accepting Decisions of Authority

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Applies and evaluates decision-making skills to engage in a variety of situations.

Extension Activities: K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12

Lessons

Organized alphabetically. Perfect if you know just what you’re looking for.

A

- Accepting Apologies

- Accepting Compliments

- Accepting Decisions of Authority

- Accepting Feedback

- Accepting Help

- Accepting the Consequences of Your Actions

- Advocating

- Apologizing

- Asking for Clarification

- Asking for Help

- Asking Questions

- Avoiding Trouble

B

- Being an Appropriate Role Model

- Being Assertive

- Being on Time and Prepared

- Being Patient

- Being Reliable

- Borrowing Others’ Belongings

C

- Choosing Good Friends

- Communicating Honestly

- Completing Assigned Tasks

- Completing Homework

- Coping with Sadness or Grief

D

- Dealing with Boredom

- Dealing with Changes

- Dealing with Embarrassment

- Dealing with Feeling Left Out

- Dealing with Mistakes or Disappointment

- Dealing with Rejection

- Developing Your Values and Beliefs

- Disagreeing with Others

E

F

G

- Gathering Information

- Getting Another Person’s Attention

- Getting the Teacher’s Attention

- Giving Compliments

- Giving Instructions

- Greeting Others

H

I

- Identifying Your Feelings

- Identifying Your Traits

- Ignoring Distractions

- Introducing Others

- Introducing Yourself

M

- Maintaining Relationships

- Making a Complaint

- Making a Request

- Making Decisions

- Making New Friends

- Managing Stress

N

O

P

- Participating in Group Activities

- Participating in Group Discussions

- Persuading Others

- Preparing for a Difficult Conversation

- Preparing for Social Situations

- Prioritizing Problems

R

- Recognizing Others’ Feelings

- Reflecting on Problems

- Reporting Emergencies

- Reporting Inappropriate Behavior

- Respecting Others’ Belongings

- Respecting Others’ Personal Information

- Respecting Others’ Privacy

- Responding to Complaints

- Responding to Conflict

- Responding to Others’ Inappropriate Behavior

- Responding to Pressure from Others

- Responding to Teasing or Bullying

- Rewarding Yourself

S

- Seeking Positive Attention

- Seeking Professional Assistance

- Setting Appropriate Boundaries

- Setting Goals

- Sharing Attention

- Sharing Your Belongings

- Showing Appropriate Affection

- Showing Empathy

- Showing Gratitude

- Showing Respect

- Showing Self-Control

- Showing Sensitivity to Others

- Showing Sportsmanship

- Solving Problems

- Starting a Conversation

- Staying on Task

- Studying for Quizzes and Tests

- Suggesting an Activity

T

U

- Using a Growth Mindset

- Using Active Listening

- Using an Appropriate Voice Volume and Tone

- Using Appropriate Humor

- Using Appropriate Language

- Using Calming Strategies

- Using Positive Self-Talk

V

Take It Further

Just a few examples of how you can embed this learning throughout the school day.

Mood Meter Visuals

Whether you’re beginning class with a temperature check, chatting about the emotions of characters in a novel, or helping an agitated student calm down, we’ve got you covered.OPEN

Calming Strategies Toolbox

Posters and visuals of various sizes can dot your hallways, classrooms, and staff lounges, reminding everyone of the calming tools they’ve learned about via Be Good People.OPEN

Skill Mini-Posters

Whether they’re hung in your classroom or used in your school’s discipline process, these mini-posters are a handy tool that summarizes Be Good People skills for students.OPEN

Think Sheets

Help students reflect on and learn from their mistakes by making Be Good People’s Think Sheets part of your school’s discipline process. Click below to print them all at once.