Strengthening Positive Parenting Practices During a Public Health Crisis

— Read on https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/covid-19-resource-center/special-education-resources/strengthening-positive-parenting-practices-during-a-public-health-crisis

Link to PDF: Here

Strengthening Positive Parenting Practices During a Public Health Crisis

PART 1: INTRODUCTION

During these times of stress and uncertainty, it can feel like our worlds have been turned upside down. This is not only true of service providers, students, and teachers, but also the families we serve. We know that increased stressors including job insecurity, housing insecurity, and generalized anxiety regarding health can impact the wellness of all members of the family system. Similarly, when one member of a family group is experiencing distress, this can cause shifts in the behavior, thinking, and relatedness of other members of the system (Bowen, 1966; Boyd-Franklin & Bry, 2012). With great levels of stress, risky parenting behaviors may come to the fore. Cumulatively, these risky parenting behaviors—even when they do not rise to the level of reportable abuse or neglect—remain a significant societal problem, and the likelihood for it to increase may be exacerbated by global crises and stressors.

In most cases, parents are able to maintain safe parenting practices, even during difficult times. A lot of parents are feeling overwhelmed and emotionally exhausted. In fact, many feel like they are not being the kind of parents they want to be or typically are. One of the first steps we can take in building partnerships is to validate and normalize parents’ reactions and experiences. Reminding parents that their feelings are normal reactions to a very abnormal situation can be invaluable. Alternatively, some parents are experiencing extraordinary distress, and they may make parenting choices that are less than optimal. In these situations, there may be a need to recognize and respond to suspicions of child maltreatment. The first step in responding to risky parenting practices is to work to enhance parenting capacity, to help families succeed and thrive. Understanding that parents and caregivers desire and want to be better parents is instrumental in helping them succeed (Prevent Child Abuse North Carolina, 2018). One of the most important roles of the school psychologist in supporting families is to mitigate risk factors and enhance protective factors. Such a framework can decrease the likelihood of abuse, maltreatment, and neglect and help families thrive.

Increasing Protective Factors

- Parental Resilience: Parenting is hard and all parents will encounter crises at some point, but parents who can weather the challenges and bounce back have safer, healthier children. School psychologists can promote parental resilience through promoting basic problem-solving skills, providing crisis support as needed, and helping parents access needed resources and community supports.

- Social Connections: Parenting is much easier if parents don’t do it all alone. Having a support network is important for a person’s social and emotional needs. Parents connected to community and friends are better able to meet children’s needs. Promoting virtual or phone contact between parents and support networks can ease parental distress, and can support and strengthen healthy parenting practices.

- Knowledge of Parenting and Child Development: Knowing what milestones are coming and how to effectively deal with them help prepare parents to care for their children. Knowledge of parenting and child development is like having directions to find your destination rather than hoping the signs you need will be clear and visible.

- Concrete Support in Times of Need: We all need a hand now and then. Parents who have dependable support and are not afraid to turn to others for help are less likely to be involved in abuse and neglect. Thus, supporting parents in reaching out to community supports can strengthen parental well-being and improve child-rearing practices.

- Social and Emotional Competence of Children: Many of the activities professionals do with children promote a child’s ability to interact positively with others and parents’ ability to nurture that development. Giving a child language to express his or her emotions, role modeling how to respond sensitively to a child, and promoting attachment and bonding between parents and children are all ways to help prevent child maltreatment (Prevent Child Abuse North Carolina, 2018).

PART 2: THE ROLE OF THE SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST

Begin with asking, “What can I do?” Many of us are feeling equally overwhelmed by the unexpected stressors brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. Reflect on how you have functioned in your role and consider how your skills can be best utilized given the limitations of remote learning. Developing your own professional action plan will help you address the mountain of need one pebble at a time, thus helping you be more effective in your work and at the same time reducing unnecessary stress and anxiety that can arise out of uncertainty.

Action Plan

- Reflect on the needs of your individual school and the children/families you serve.

- Consider your role and function as a school psychologist within the present societal context.

- Identify ways in which you can support families and children proactively.

- Identify ways in which you can support teachers or other school officials as they engage with their students.

- Create weekly benchmarks and regularly review whether you are making progress toward goals.

As schools operate through a remote learning format, school psychologists can support families in managing stressors through both prevention and intervention frameworks. Our unique skill set equips us to examine our schools from the perspective of individuals and communities and help identify and connect those in need with the support necessary to help families maintain their emotional health. Be a STAR during this challenging time, and use this parent training practice to support the families you are working with.

| Teach Your Parents to Stop, Think, Act, and Reflect |

Parent Response/Feedback to the Activity |

| S |

Stop: (A) Have the parent identify when they are about to lose their temper with their kids. Coach the parent to take a brief break before responding to their children. (B) Ask the parent: What has been causing you to “lose your cool” recently in your interactions with your kid(s)? |

(A)

(B) |

| T |

Think: (A) Have the parent identify alternative manners to respond to challenging child behaviors. (B) Ask the parent: How can you respond differently to your child(ren) when they behave in ways you believe are inappropriate? |

(A)

(B) |

| A |

Act: Have the parent try out their new strategy. (A) How did things go when you tried your new strategy? |

(A) |

| R |

Reflect: Have the parent reflect on what went right and what can be improved when they tried out their new response to their children’s challenging behavior(s).(A) What can you do differently next time to more effectively parent your child(ren) when they are engaging in this challenging behavior(s)? |

(A) |

PART 3: PRACTICAL ACTION STEPS

Parents want what is best for their children. Unfortunately, stress and stressors can get in the way and impede healthy parenting. The COVID-19 pandemic is resulting in huge stress for families. Direct and indirect fallout from the pandemic can sometimes result in parents interacting with their children in ways they may later regret. Here are some tips school psychologists can share with stressed out parents during these difficult times.

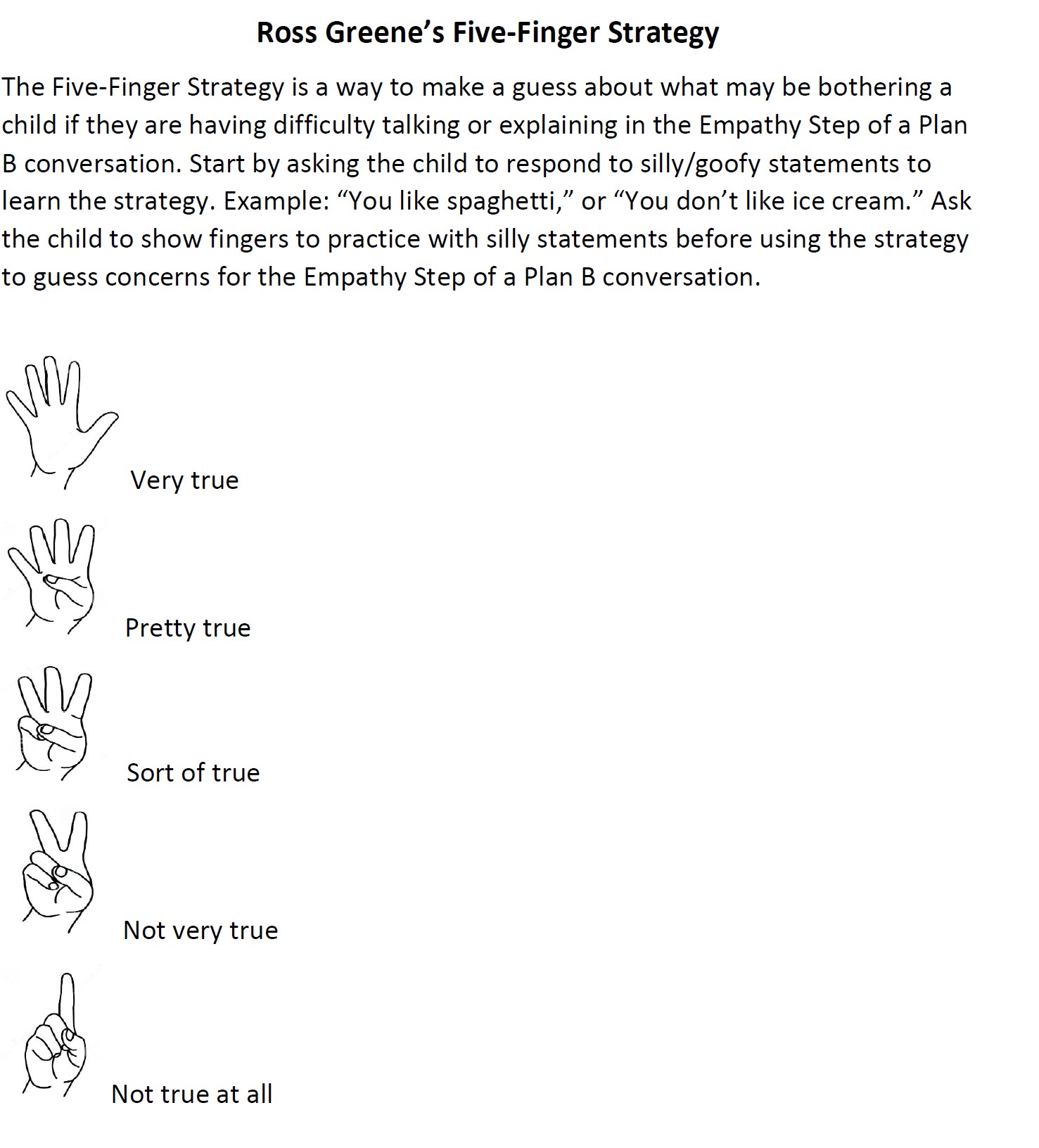

Assessing Parenting Stress Levels

How parents handle stress, including the fallout from COVID-19, can contribute to risky parenting behaviors. One way to help parents is to teach them self-monitoring of their distress. Parents can rate their stress level, through a simple thermometer metaphor. Teach parents to ask themselves: “On a scale of 1–10, how stressed out am I feeling at the moment?” Have the parent identify two or three simple coping skills they regularly use, which they could use quickly and easily to destress. This includes brief activities such as listening to music, playing a video game, or taking a walk in the backyard. Set up a system where parents complete this self-assessment a few times throughout the day. When stress levels are high, have parents use one of their identified coping skills. You can find a feelings thermometer and many useful cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) worksheets online here. Also, reputable CBT and psychoeducation worksheets that can be helpful when working with parents and families can be found here.

In addition to assessing current stress levels, there are other steps we can take to better understand and address the needs of the families school psychologists support. As we seek to support all families, it may become apparent that specific families need more direct care. Your parents may find websites on how to start an individual mindfulness practice or on parental mindfulness helpful. To better understand these specific contextual needs of our families, consider the following.

- Assess parent/family stress and resources: Conduct a brief needs assessment to identify primary areas of concern (food insecurity, housing insecurity, stress management, managing remote learning, family dynamics). A needs assessment is a systematic process to identify or determine family needs, and to identify barriers impeding access to needed resources. Identifying the discrepancy between the current condition and the desired one should be prioritized by you as the school psychologist, so that you can provide the tools and resources that can best mitigate the discrepancies between current and desired conditions.

- Safety Plan: Support the family in developing a safety plan. This plan should clearly describe challenges to safety of family members and steps that can be taken to manage threats to a parent or child’s safety. A safety plan is designed to mitigate threats to a family member’s safety using the least intrusive means possible. Here is an example of a safety plan.

- Check in: Identify school personnel or other individuals who can conduct regular meetings with the family to assess family temperature and continue to clarify strengths and needs. This could be school or community social workers, case workers, or a trusted professional or community member with the training and expertise to help strengthen families.

Promote Positive Communication

Good communication between parents and children is critical for developing a positive parent–child relationship and for subsequent development. If you notice coercive, concerning, or poor quality communication or parenting behaviors occurring in the family home, work with the parent(s) to emphasize basic parent training strategies. Basic parent training strategies you can share with parents you are working with include:

- Praise: Teach parents to praise their kids regularly for demonstrating a strong effort or doing something right. Remind the parents you are supporting that the more frequently they praise a behavior, the more likely it is their child will behave the same way again.

- Mindful Parenting: Promote the value of present moment engagement as it pertains to parent–child interactions. Emphasize to parents that providing their full attention to their children, to what is happening in the here-and-now, will help them better understand what their children are thinking and feeling, lessen disagreement, and strengthen the parent–child bond.

- Active Listening: Active listening is a useful tool to promote positive parenting practices. When school psychologists provide psychoeducation on active listening, parents learn how to listen, both verbally and nonverbally, to strengthen their relationships with their children and others. Providing psychoeducation to parents regarding how to reflect back the words, sentiments, or emotions expressed by the child can make active listening particularly effective in promoting communication.

- Child-Led Play or Special Time Together: Reinforce to parents the power of time spent together with their children. Regular (even short) periods of play with younger children or parent–child activities with older children and adolescents can strengthen communication and the overall parent–child relationship.

- Ignoring: Ignoring can help quickly end attention-seeking behaviors such as whining or tantrums. Ignoring is an active practice. This will require ongoing work and support with parents. However, teaching parents to ignore attention seeking behaviors can help end challenging behaviors by the child early, before they escalate and cause upheaval within the household. You as the school psychologist should work with the parent to teach them how to remove attention from the child and the negative behavior(s) they are exhibiting, to promote stress and relaxation within the household.

PART 4: INTENSIVE AND INDIVIDUALIZED INTERVENTION

Even with robust support and interventions in place, there is a possibility that a small portion of the populations we serve may need more intensive interventions. The number of families who are engaging in risky parenting behaviors and who are at risk for engaging in child maltreatment or abuse may increase during times of global crisis. Intensive, individualized interventions—either immediately or at a later date—may be necessary for some families. When appropriate, the school psychologist may be able to provide these services directly. Your role also may include consultation and referral of the family to more focused and specialized clinical and community-based supports. While there are a wide range of choices to consider in intensive interventions, a sample of evidence-based interventions that may have utility in supporting families in distress who may be engaging in risky parenting behaviors include the following.

Interventions Focused on Young Children Birth to Age 5

- Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC)

- Child–Parent Psychotherapy (CPP)

- Parent–Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT)

- Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care for Preschoolers (MTFC)

- The Incredible Years* (IY)

- Triple-P* (PPP)

*Modules and research also support these programs with older children (i.e., middle childhood and adolescence).

Interventions Focused on Middle Childhood and Adolescence

- Trauma-Focused Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy

- Alternatives for Families: A Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy

- Multisystemic Therapy – for Child Abuse and Neglect

- DBT Skills

PART 5: ENSURING CHILD AND FAMILY SAFETY

The COVID-19 pandemic is impacting families in unalterable ways. For many families, loss of employment, social isolation, and myriad other challenges brought forward through the pandemic are increasing family distress. These challenges will likely continue and possibly even worsen in the coming months. School psychologists will encounter family dynamics in new and profound manners through teletherapy. While most encounters will be adaptive, healthy, or even humorous, others may expose the school psychologist to the escalating stress and challenges experienced by many families. At times such unwitting encounters may even result in school psychologists who witness events, interactions, or behaviors that rise to the level of a reportable offense. Remember, as school psychologists we are all mandated reporters. Thus, we must be prepared to contact our statewide child protective services office should we observe anything in the home through teletherapy services that raises a reasonable suspicion of child maltreatment.

Parents and families generally want what is best for their children. When parents and caregivers are under duress, their ability to engage in healthy parenting practices may decline. It is important that we consider the robust and broad risk and protective factors that may impact child rearing and caregiving capabilities. During times of global health or related crises, such as COVID-19, school psychologists play a key role in strengthening families. With their breadth and depth of knowledge, school psychologists must strive to use their skills to promote healthy parenting behaviors.

RESOURCES: Help and Safety Contacts/Hotlines

References

Boyd-Franklin, N., & Bry, B. H. (2012). Reaching out in family therapy: Home-based, school, and community interventions. Guilford Press.

Bowen, M. (1966). The use of family theory in clinical practice. Comprehensive psychiatry, 7(5), 345–374.

Prevent Child Abuse, North Carolina. (2018). Recognizing and Responding to Suspicions of Child Maltreatment: A Training for Adults Working with Children and Families. (Retrieved from https://preventchildabusenc-lms.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/RR-full_2018.pdf)

Contributors: Kirby Wycoff, Michele Messer, and Aaron Gubi

Please cite as: National Association of School Psychologists. (2020). Strengthening positive parenting practices during a public health crisis [handout]. Author.

© 2020, National Association of School Psychologists, 4340 East West Highway, Suite 402, Bethesda, MD 20814, 301-657-0270, http://www.nasponline.org