I ran across this Nemours website by accident looking for developmental reading resources and I found so much more. I hope you find it as useful as I have in looking at reading and health subjects in a very concise and accessible format.

Monthly Archives: October 2018

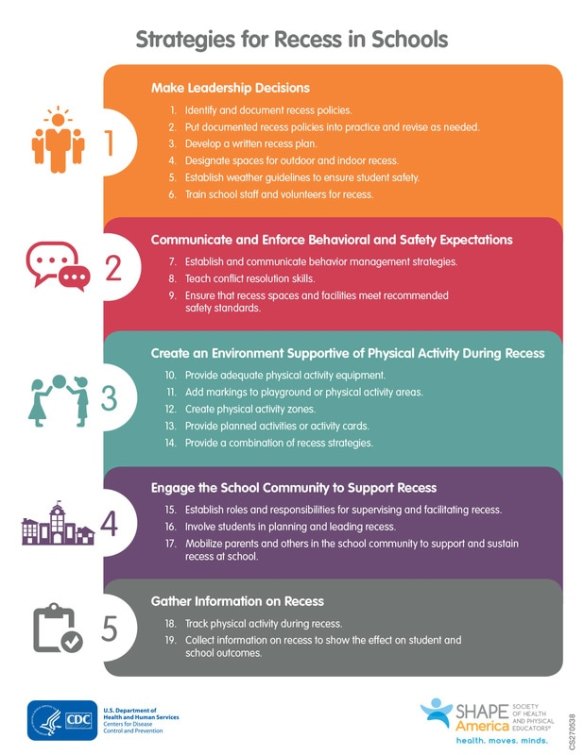

Making the Most of Recess

Good Reads

- Building a Culture of Health Through Safe and Healthy Elementary School Recess

- Dr. Ken Shore’s Classroom Problem Solver Playground Behaviors

- A Parent’s Guide to Conflict Resolution & Peer Mediation (School Example)

- Playground Management Plan (Very Clear and Comprehensive)

- Good practical collection of tools utilizing the “Peace Program”

- The Importance of Outdoor Play and Its Impact on Brain Development In Children

- The Importance of Recess, Play, and Active Classrooms

- A Research-Based Case for Recess

- Give me a Break! Can Strategic Recess Scheduling Increase On-Task Behavior for First Graders?

- Is the Elimination of Recess in School a Violation of a Child’s Basic Human Rights?

- Playing Fair: The Contribution of High-Functioning Recess to Overall School Climate in Low-Income Elementary Schools

- Recess in Elementary School: What Does the Research Say?

- School Recess and Group Classroom Behavior

- School Recess and Social Development

- The Crucial Role of Recess in Schools

- The Role of Recess in Children’s Cognitive Performance and School Adjustment

What you promote by creating a positive recess experience:

Outdoor Play Allows a School-Aged Child to:

-Increase the flow of blood to the brain. The blood delivers oxygen and glucose, which the brain needs for heightened alertness and mental focus.-Build up the body’s level of brain-derived neurotrophic factor or BDNF, BDNF causes the brain’s nerve cells to branch out, join together and communicate with each other in new ways, which leads to your child’s openness to learning an more capacity for knowledge

-Build new brain cells in a brain region called dentate gyrus, which is linked

with memory and memory loss.-Improves their ability to learn.

-Increase the size of basal ganglia, a key part of the brain that aids in

maintaining attention and “executive control,” or the ability to coordinate

actions and thoughts crisply.-Strengthen the vestibular systems that create spatial awareness and mental

alertness. This provides your child with the framework for reading and other

academic skills-Help creativity

Raise Smart Kid (2015). The Benefits of Exercise On Your Kid’s Brain.

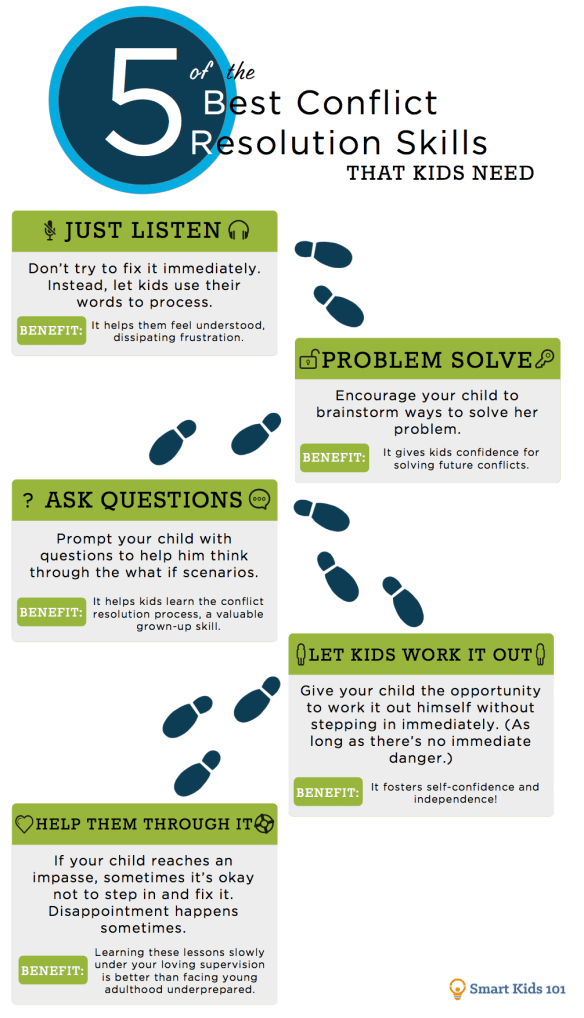

Addressing Conflict on the Yard

Conflict is normal

Conflict is a normal part of children’s lives. Having different needs or wants, or wanting the same thing when only one is available, can easily lead children into conflict with one another. “She won’t let me play,” “He took my …”, “Tom’s being mean!” are complaints that parents, carers and school staff often hear when children get into conflict and are unable to resolve it. Common ways that children respond to confl ict include arguing and physical aggression, as well as more passive responses such as backing off and avoiding one another.

When conflict is poorly managed it can have a negative impact on children’s relationships, on their self-esteem and on their learning. However, teaching children the skills for resolving conflict can help signifi cantly. By learning to manage conflict effectively, children’s skills for getting along with others can be improved. Children are much happier, have better friendships and are better learners at school when they know how to manage conflict well.

Different ways of responding to conflict

Since children have different needs and preferences, experiencing conflict with others is unavoidable. Many children (and adults) think of conflict as a competition that can only be decided by having a winner and a loser. The problem with thinking about conflict in this way is that it promotes win-lose behaviour: children who want to win try to dominate the other person; children who think they can’t win try to avoid the conflict. This does not result in effective conflict resolution.

Win-lose approaches to conflict

Children may try to get their way in a conflict by using force. Some children give in to try to stop the conflict, while others try to avoid the situation altogether. These different styles are shown below. When introducing younger children to the different ways that conflicts can be handled, talking about the ways the animals included as examples below might deal with conflict can help their understanding. It introduces an element of fun and enjoyment.

Conflict style Animal example Child’s behaviour Force Shark, bull, lion Argues, yells, debates, threatens, uses logic to impose own view. Give in Jelly fish, teddy bear Prevents fights, tries to make others happy. Avoid Ostrich, turtle Thinks or says: “I don’t want conflict.” Distracts, talks about something else, leaves the room or the relationship. Sometimes these approaches appear to work in the short-term, but they create other sets of problems. When children use force to win in a conflict it creates resentment and fear in others. Children who ‘win’ using this approach may develop a pattern of dominating and bullying others to get what they want. Children who tend to give in or avoid conflict may lack both confidence and skills for appropriate assertive behaviour. They are more likely to be dominated or bullied by others and may feel anxious and negative about themselves.

It is possible instead to respond to conflict in positive ways that seek a fair outcome. Instead of being seen as a win-lose competition, conflict can be seen as an opportunity to build healthier and more respectful relationships through understanding the perspectives of others.

Win-some lose-some: Using compromise to resolve conflict

Adults have a significant impact on how children deal with conflict. Often adults encourage children to deal with conflict by compromising. Compromising means that no-one wins or loses outright. Each person gets some of what they want and also gives up some of what they want. Many children learn how to compromise as they grow and find ways to negotiate friendships. It is common around the middle of primary school for children to become very concerned with fairness and with rules as a way of ensuring fairness. This may correspond with an approach to resolving conflict that is based on compromise.

Conflict style Animal example Child’s behaviour Compromise Fox I give a bit and expect you to give a bit too. Win-win: Using cooperation to resolve conflict

Using a win-win approach means finding out more about the problem and looking together for creative solutions so that everyone can get what they want.

Conflict style Animal example Child’s behaviour Sort out the problem (Win-win)

Owl Discover ways of helping everyone in the conflict to get what they want. Skills required for effective conflict resolution

Effective conflict resolution requires children to apply a combination of well-developed social and emotional skills. These include skills for managing feelings, understanding others, communicating effectively and making decisions. Children need guidance and ‘coaching’ to learn these skills. Learning to use all the skills effectively in combination takes practice and maturity. However, with guidance children can begin to use a win-win model and gradually develop their abilities to resolve conflicts independently.

Skill What to encourage children to learn

- Manage strong emotions

- Use strategies to control strong feelings

- Verbally express own thoughts and feelings

- Identify and communicate thoughts and feelings

- Identify the problem and express own needs

- Talk about their own wants/needs/fears/concerns without demanding an immediate solution

- Understand the other person’s perspective

- Listen to what the other person wants/needs

- Understand the other person’s fears/concerns

- Understand without having to agree

- Respond sensitively and appropriately

- Generate a number of solutions to the problem

- Think of a variety of options

- Try to include the needs and concerns of everyone involved

- Negotiate a win-win solution

- Be flexible

- Be open-minded

- Look after own needs as well as the other person’s needs (be assertive)

Guiding children through the steps of conflict resolution

1. Set the stage for WIN-WIN outcomes

Conflict arises when people have different needs or views of a situation. Make it clear that you are going to help the children listen to each other’s point of view and look for ways to solve the problem that everyone can agree to.

- Ask, “What’s the problem here?” Be sure to get both sides of the story (eg “He won’t let me have a turn” from one child, and “I only just started and it’s my game,” from another).

- Say, I’m sure if we talk this through we’ll be able to sort it out so that everyone is happy.”

2. Have children state their own needs and concerns

The aim is to find out how each child sees the problem. Help children identify and communicate their needs and concerns without judging or blaming.

- Ask, “What do you want or need? What are you most concerned about?”

3. Help children listen to the other person and understand their needs and concerns

In the heat of conflict it can be difficult to understand that the other person has feelings and needs too. Listening to the other person helps to reduce the conflict and allows children to think of the problem as something they can solve together.

- Ask, “So you want to have a turn at this game now because it’s nearly time to go home? And you want to keep playing to see if you can get to the next level?”

- Show children that you understand both points of view: “I can understand why you want to get your turn. I can see why you don’t want to stop now.”

4. Help children think of different ways to solve the problem

Often children who get into conflict can only think of one solution. Getting them to think of creative ways for solving the conflict encourages them to come up with new solutions that no-one thought of before. Ask them to let the ideas flow and think of as many options as they can, without judging any of them.

- Encourage them: “Let’s think of at least three things we could do to solve this problem.”

5. Build win-win solutions

Help children sort through the list of options you have come up with together and choose those that appear to meet everybody’s needs. Sometimes a combination of the options they have thought of will work best. Together, you can help them build a solution that everyone agrees to.

- Ask: Which solution do you think can work? Which option can we make work together?

6. Put the solution into action and see how it works

Make sure that children understand what they have agreed to and what this means in practice.

- Say, “Okay, so this is what we’ve agreed. Tom, you’re going to show Wendy how to play the game, then Wendy, you’re going to have a try, and I’m going to let you know when 15 minutes is up.”

Key points for helping children resolve conflict

The ways that adults respond to children’s conflicts have powerful effects on their behaviour and skill development. Until they have developed their own skills for managing conflict effectively most children will need very specific adult guidance to help them reach a good resolution. Parents, carers and teaching staff can help children in sorting out conflict together, by seeing conflict as a shared problem that can be solved by understanding both points of view and finding a solution that everyone is happy with.

Guide and coach

When adults impose a solution on children it may solve the conflict in the short term, but it can leave children feeling that their wishes have not been taken into account. Coaching children through the conflict resolution steps helps them feel involved. It shows them how effective conflict resolution can work so that they can start to build their own skills.

Listen to all sides without judging

To learn the skills for effective conflict resolution children need to be able to acknowledge their own point of view and listen to others’ views without fearing that they will be blamed or judged. Being heard encourages children to hear and understand what others have to say and how they feel, and helps them to learn to value others.

Support children to work through strong feelings

Conflict often generates strong feelings such as anger or anxiety. These feelings can get in the way of being able to think through conflicts fairly and reasonably. Acknowledge children’s feelings and help them to manage them. It may be necessary to help children calm down before trying to resolve the conflict.

Remember

- Praise children for finding a solution and carrying it out.

- If an agreed solution doesn’t work out the first time, go through the steps again to understand the needs and concerns and find a different solution.

The information in this resource is based on Wertheim, E., Love, A., Peck, C. & Littlefield, L. (2006). Skills for resolving conflict (2nd Edition). Melbourne: Eruditions Publishing.

Web: Source

Reactive Attachment Disorder at School

Students with Reactive Attachment Disorder often need a unique plan to help find them success at school. This post aims to help bring understanding and ideas to support your students with Reactive Attachment Disorder.

What it can look like-

Twenty RAD symptoms by Todd Friel- Source

- Superficially charming. Never real. Always fake. Good enough to fool people who don’t know them well. Used extensively for manipulation purposes. Examples: I love you mommy, all super sweet, after being verbally and physically abusive to mommy for days because RAD just realized they want something only mommy can give to them. Or, charming the pants off of a stranger, then telling their “poor orphan” story so the person will feel sorry for them then buy or give them what they want.

- Lack of eye contact. They will not engage unless they want something. They will only have direct eye contact when they want something from you and they are trying to gauge your reaction to their request or behavior. If you begin a conversation with them they will look everywhere except at you.

- Indiscriminately affectionate with strangers. Ours point blank told us that they trusted the stranger they met that afternoon more than they trusted us, their parents. Hugging and snuggling with complete strangers within moments of meeting them is very common. Stroking other people including their hair and rubbing their hands over the strangers back and shoulders. They will grab and hold hands. They have ZERO natural boundaries. In fact this was a symptom of RAD we were unaware of when we met our RAD’s who were overly affectionate with us immediately upon meeting us. Red flag.

- Not affectionate on parents’ terms. Only when RAD wants something will they say things like I’m sorry, I love you, or show any signs of affection including using terms such as mom or dad. I learned that when I heard one of them say “mom” to be on alert because they were attempting to manipulate me. Sometimes we gave in on something they wanted simply to see a glimpse of the child/teen we thought they were all the while knowing once they get what they want they will go back to their same bad behavior and we will be disappointed once again.

- Destructive to self, others, animals, and material things. I could write a book about this – oh wait! I did! Self-harming is something many RAD’s do, many times to gain attention. Above all else they want all attention focused on themselves. We found the majority of the destruction from our RAD’s was aimed at hurting mom who they viewed as the enemy. Anything mom cared for became a target. That included biological children, pets, or anything that’s important to mom. If I buy the puppy a new toy it is sure to come up missing within hours. If my bio daughter gets a new notebook for school something of hers will go missing or the new notebook will have slits through it from a knife. Nothing is sacred. As mom I am very careful to what or whom I pay any special attention because there will be repercussions. If there is a baby or toddler in the home they need to be watched 24/7 to keep them from being harmed.

- Cruelty to animals. RAD’s can be very cruel. They love to torment those who are weaker than they are to show their superiority, and even more so if this animal is one that I, their enemy, shows any affection whatsoever. One woman who rescued cats found her adopted daughter throwing the cats against the wall to see it they would break. They did. Many of them died. There was zero remorse. She thought it was funny. And when she saw her mom crying it made her even happier.

- Lying about the obvious. Here is an example that happened over and over again in our home. I see RAD take something that doesn’t belong to them. I tell them to put it back because it isn’t theirs. RAD states they didn’t take it even though it is in their hand. I say there it is right in your hand. This will go on forever unless you threaten to take something of theirs from them. No amount of reasoning will do anything except add to the frustration. After putting up camera’s in my home office to keep them from stealing we showed them the video’s of them going into my purse and taking money. They all denied it vehemently even though the video clearly showed them putting the money into their pockets. They were so angry that we accused them that they slammed out the front door and we didn’t see them until the police brought them home three days later. Then adding insult to injury when brought home they told the police they ran away because we were stealing their money.

- Stealing. Constant. Anything of perceived value. From us. From school mates. From teachers. From stores. From gas stations. From friends. From strangers. With zero remorse or admittance even when caught. On the other hand when someone steals something from them (which happened to one of our RAD’s at school). After he noticed that $5 was taken from his jacket he blew up and screamed profanities until he had to be physically restrained and I was called to pick him up where he continued to scream at me about his $5. This was the same boy who stole hundreds of dollars from us. When I attempted to help him empathize with us who he had stolen from he simply told me it was not the same and continued to rant for hours about his $5.

- No impulse controls. What they want, they take. What they want to do, they do. They care nothing about consequences and in fact will be surprised if caught and then mad they got caught for something they think is no big deal. They completely turn the tables until everything, including what they did, is someone else’s fault. It is narcissism gone wild. They can only think about themselves and what they want. You cannot reason with this mentality.

- Lack of conscience. As stated in several examples above, they have no reality of anything ever being their responsibility or fault. They will never feel badly about something they’ve done. Sometimes they will act as if they feel badly and say they are sorry but only if they think it will get them out of trouble. Manipulation tactic. One of our adopted RAD’s is back in his home country. He messages me and tells me he is sorry for molesting our 15-year-old daughter. Then he asks me to help him get back to America. One time I flat out said to him that the only reason he was saying he was sorry was so that I would help him. He agreed then asked if I would help him anyway.

- Abnormal eating patterns. They can eat enormous amounts of food or no food at all for days. They will eat strange combinations like an entire container of sour cream with a cup of sugar on top. They will ask for a certain food and once made will refuse to eat it telling you it looks like garbage. They will steal food from a local store and we’ll find it rotting, uneaten, in their room. If you put something in front of them they don’t like that day (they liked it last week) they will spit on it and me, asking why I feed them such garbage. (This is homemade from scratch food.) They will take the sandwich made with homemade bread and throw it in the garbage at school and then tell everyone we are starving them. We will wake up one morning and find the refrigerator was cleaned out of all the food we planned to serve that day. Later we’ll find empty containers in their room and uneaten food smashed under their mattress.

- Poor peer relationships. Making friends for most RAD’s is literally impossible. It goes back to it’s all about them. No one, even another small child who starts out as a friend, will put up with that behavior for long. RAD will keep up the relationship as long as there is something in it for them. After that they will walk away without a second thought. Our RAD’s even turned on each other when it suited them. There is no loyalty. And zero understanding when RAD tries to rekindle the relationship and the other person wants nothing to do with RAD. RAD doesn’t comprehend that it was them that ruined the relationship and the other person doesn’t want to get burned a second time.

- Preoccupation with fire. Constant talk of burning down the house, burning the car, burning everything meaningful to the family, and even burning the house with the family inside. Playing with matches and lighters. Drawing vivid pictures of burning buildings. Filling trash cans with combustibles and lighting them on fire. There are numerous stories of homes being burned to the ground by their RAD child or teen. Fire and RAD are a dangerous mixture.

- Preoccupation with blood and gore. If RAD is not watching porn on their (stolen) phone they will migrate to the most violent shows possible. They spend hours watching the news and the worse it is the more they are enthralled with it. A fellow adoptive mom said that her RAD daughter would only watch the beginning of a particular show because she liked watching the murder happen. The mom said she liked watching the criminals get caught and brought to justice. RAD said, “That’s boring.” They will draw pictures with lots of blood and scenes of murder. One mom found a picture drawn by RAD daughter of RAD standing over the mom while mom was sleeping with a bloody red knife in her hands and blood all over the room.

- Preoccupation with bodily functions. Painting with feces is common. There are even groups on social media where this is their main focus it is so common. Urinating on things of importance, into heating vents, and on furniture and even walls to ruin them. However, this bodily function doesn’t mean they have good hygiene and in most cases they have just the opposite. They will refuse to take showers or wash their hair. If they smell at school please know we do our best to make them wash but I cannot go into a shower with an older child or teenager to make sure they wash with soap and water.

- Persistent nonsense questions, chatter, and senseless noises. Non-stop questions about mindless things. Constant “why” questions where they don’t care one bit about the answer but are just taking up your time. They want to be the center of attention at all times. And if it’s not questions it is meaningless chatter or noise. Imagine someone who refuses to get more than two feet from you who constantly clicks their tongue over and over for five or six hours just because they know it makes you crazy. And if you ask them to stop, they just do it louder because they know they are achieving their goal. Or how about listening to non-stop screaming. They scream until they can’t scream anymore because they lose their voice. Once healed they start screaming all over again.

- Non-stop demanding of attention. RAD must be the center of attention at all times. If someone or something else has your attention they will force themselves between in any way they can. One dad told this story. He was playing cards with another child at the kitchen table. RAD attempted to sit on dad’s lap – this is a 16-year-old male – and when that didn’t work he pulled up a chair so close it was touching dad’s chair and leaned heavily against dad, talking constantly and disrupting through the entire game and even putting his feet up on the table, asking dad to rub his feet. AND this was AFTER dad asked RAD to play the game with him and RAD retorted with profanity that he hates playing games and stomped off to his room. It was only after dad started playing with the other child that RAD became interested.

- Triangulation of adults. I wrote several sections in Adoption Combat Zone on triangulation. Most times this is pitting dad against mom but triangulation can occur with any adult who the RAD can manipulate including fellow church members, teachers, neighbors, extended family members, etc. The goal for the RAD is to manipulate someone to take their side in things. Triangulation occurs when RAD is allowed to come between adults. To one side they show their worst and the other, only their best. One person sees a sweet, adorable, perfect child/teen, the other sees someone who is trying to destroy them through whatever means possible. All this is done in order to get the life the RAD wants, one where they are in total control.

- False allegations of abuse. This is more common than any sane person would think and I’ve written much about it in the book. This is the number one go-to for RAD’s to get back at anyone who is not giving them what they want or to try and get what they want. We were turned into the authorities by our RAD’s several times for made-up abuses simply for not allowing them to keep a phone they stole and sit up all night watching porn on said phone. Mad at it being taken away they went to school the next day and reported us for abuse. Or when they feel threatened because they were caught doing something wrong they will turn in someone else in order to take the heat off themselves. They are fantastic story tellers.

- Creating chaos. RAD’s are experts at creating commotion so they can be the center of attention whether it be something like the dad playing a game above or something more serious such as starting a fire in your kitchen so they can go through your purse to steal your cash and credit cards. They will disrupt family dinners and outings. They love arguing and the louder it gets, the better.

This video by Todd Friel is a must-watch for anyone who is a friend, teacher, or family member of someone who has adopted a RAD child/teen. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5ypmGTGGN7A&t=2s

If you are a family with a RAD child or teen here is an excellent resource for you: http://instituteforattachment.org/

Articles

Reactive Attachment Disorder – Fact Sheet

Children with Reactive Attachment Disorder FACT SHEET FOR EDUCATORS By Connie Hornyak, LCSW

Reactive Attachment Disorder: A Summary for Teachers Jessica Murphy, MSW, LICSW

Back to School With Reactive Attachment Disorder: 10 Things to do – by- JOHN M. SIMMONS

DEFINITIONS

MAYO CLINIC

Overview

Reactive attachment disorder is a rare but serious condition in which an infant or young child doesn’t establish healthy attachments with parents or caregivers. Reactive attachment disorder may develop if the child’s basic needs for comfort, affection and nurturing aren’t met and loving, caring, stable attachments with others are not established.

With treatment, children with reactive attachment disorder may develop more stable and healthy relationships with caregivers and others. Treatments for reactive attachment disorder include psychological counseling, parent or caregiver counseling and education, learning positive child and caregiver interactions, and creating a stable, nurturing environment.

Symptoms

Reactive attachment disorder can start in infancy. There’s little research on signs and symptoms of reactive attachment disorder beyond early childhood, and it remains uncertain whether it occurs in children older than 5 years.

Signs and symptoms may include:

- Unexplained withdrawal, fear, sadness or irritability

- Sad and listless appearance

- Not seeking comfort or showing no response when comfort is given

- Failure to smile

- Watching others closely but not engaging in social interaction

- Failing to ask for support or assistance

- Failure to reach out when picked up

- No interest in playing peekaboo or other interactive games

When to see a doctor

Consider getting an evaluation if your child shows any of the signs above. Signs can occur in children who don’t have reactive attachment disorder or who have another disorder, such as autism spectrum disorder. It’s important to have your child evaluated by a pediatric psychiatrist or psychologist who can determine whether such behaviors indicate a more serious problem.

Causes

To feel safe and develop trust, infants and young children need a stable, caring environment. Their basic emotional and physical needs must be consistently met. For instance, when a baby cries, the need for a meal or a diaper change must be met with a shared emotional exchange that may include eye contact, smiling and caressing.

A child whose needs are ignored or met with a lack of emotional response from caregivers does not come to expect care or comfort or form a stable attachment to caregivers.

It’s not clear why some babies and children develop reactive attachment disorder and others don’t. Various theories about reactive attachment disorder and its causes exist, and more research is needed to develop a better understanding and improve diagnosis and treatment options.

Risk factors

The risk of developing reactive attachment disorder from serious social and emotional neglect or the lack of opportunity to develop stable attachments may increase in children who, for example:

- Live in a children’s home or other institution

- Frequently change foster homes or caregivers

- Have parents who have severe mental health problems, criminal behavior or substance abuse that impairs their parenting

- Have prolonged separation from parents or other caregivers due to hospitalization

However, most children who are severely neglected don’t develop reactive attachment disorder.

Complications

Without treatment, reactive attachment disorder can continue for several years and may have lifelong consequences.

Some research suggests that some children and teenagers with reactive attachment disorder may display callous, unemotional traits that can include behavior problems and cruelty toward people or animals. However, more research is needed to determine if problems in older children and adults are related to experiences of reactive attachment disorder in early childhood.

Prevention

While it’s not known with certainty if reactive attachment disorder can be prevented, there may be ways to reduce the risk of its development. Infants and young children need a stable, caring environment and their basic emotional and physical needs must be consistently met. The following parenting suggestions may help.

- Take classes or volunteer with children if you lack experience or skill with babies or children. This will help you learn how to interact in a nurturing manner.

- Be actively engaged with your child by lots of playing, talking to him or her, making eye contact, and smiling.

- Learn to interpret your baby’s cues, such as different types of cries, so that you can meet his or her needs quickly and effectively.

- Provide warm, nurturing interaction with your child, such as during feeding, bathing or changing diapers.

- Offer both verbal and nonverbal responses to the child’s feelings through touch, facial expressions and tone of voice.

Diagnosis

A pediatric psychiatrist or psychologist can conduct a thorough, in-depth examination to diagnose reactive attachment disorder.

Your child’s evaluation may include:

- Direct observation of interaction with parents or caregivers

- Details about the pattern of behavior over time

- Examples of the behavior in a variety of situations

- Information about interactions with parents or caregivers and others

- Questions about the home and living situation since birth

- An evaluation of parenting and caregiving styles and abilities

Your child’s doctor will also want to rule out other psychiatric disorders and determine if any other mental health conditions co-exist, such as:

- Intellectual disability

- Other adjustment disorders

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Depressive disorders

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DMS-5)

Your doctor may use the diagnostic criteria for reactive attachment disorder in the DSM-5, published by the American Psychiatric Association. Diagnosis isn’t usually made before 9 months of age. Signs and symptoms appear before the age of 5 years.

Criteria include:

- A consistent pattern of emotionally withdrawn behavior toward caregivers, shown by rarely seeking or not responding to comfort when distressed

- Persistent social and emotional problems that include minimal responsiveness to others, no positive response to interactions, or unexplained irritability, sadness or fearfulness during interactions with caregivers

- Persistent lack of having emotional needs for comfort, stimulation and affection met by caregivers, or repeated changes of primary caregivers that limit opportunities to form stable attachments, or care in a setting that severely limits opportunities to form attachments (such as an institution)

- No diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder

Treatment

Children with reactive attachment disorder are believed to have the capacity to form attachments, but this ability has been hindered by their experiences.

Most children are naturally resilient. And even those who’ve been neglected, lived in a children’s home or other institution, or had multiple caregivers can develop healthy relationships. Early intervention appears to improve outcomes.

There’s no standard treatment for reactive attachment disorder, but it should involve both the child and parents or primary caregivers. Goals of treatment are to help ensure that the child:

- Has a safe and stable living situation

- Develops positive interactions and strengthens the attachment with parents and caregivers

Treatment strategies include:

- Encouraging the child’s development by being nurturing, responsive and caring

- Providing consistent caregivers to encourage a stable attachment for the child

- Providing a positive, stimulating and interactive environment for the child

- Addressing the child’s medical, safety and housing needs, as appropriate

Other services that may benefit the child and the family include:

- Individual and family psychological counseling

- Education of parents and caregivers about the condition

- Parenting skills classes

Controversial and coercive techniques

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the American Psychiatric Association have criticized dangerous and unproven treatment techniques for reactive attachment disorder.

These techniques include any type of physical restraint or force to break down what’s believed to be the child’s resistance to attachments — an unproven theory of the cause of reactive attachment disorder. There is no scientific evidence to support these controversial practices, which can be psychologically and physically damaging and have led to accidental deaths.

If you’re considering any kind of unconventional treatment, talk to your child’s psychiatrist or psychologist first to make sure it’s evidence based and not harmful.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this disease.

Coping and support

If you’re a parent or caregiver whose child has reactive attachment disorder, it’s easy to become angry, frustrated and distressed. You may feel like your child doesn’t love you — or that it’s hard to like your child sometimes.

These actions may help:

- Educate yourself and your family about reactive attachment disorder. Ask your pediatrician about resources or check trusted internet sites. If your child has a background that includes institutions or foster care, consider checking with relevant social service agencies for educational materials and resources.

- Find someone who can give you a break from time to time. It can be exhausting caring for a child with reactive attachment disorder. You’ll begin to burn out if you don’t periodically have downtime. But avoid using multiple caregivers. Choose a caregiver who is nurturing and familiar with reactive attachment disorder or educate the caregiver about the disorder.

- Practice stress management skills. For example, learning and practicing yoga or meditation may help you relax and not get overwhelmed.

- Make time for yourself. Develop or maintain your hobbies, social engagements and exercise routine.

- Acknowledge it’s OK to feel frustrated or angry at times. The strong feelings you may have about your child are natural. But if needed, seek professional help.

Preparing for your appointment

You may start by visiting your child’s pediatrician. However, you may be referred to a child psychiatrist or psychologist who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of reactive attachment disorder or a pediatrician specializing in child development.

Here’s some information to help you get ready and know what to expect from your doctor.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list of:

- Any behavior problems or emotional issues you’ve noticed, and include any signs or symptoms that may seem unrelated to the reason for your child’s appointment

- Key personal information, including any major stresses or life changes that you or your child have been through

- All medications, vitamins, herbal remedies or other supplements your child is taking, including the dosages

- Questions to ask your child’s doctor to make the most of your time together

Some basic questions to ask your doctor may include:

- What is likely causing my child’s behavior problems or emotional issues?

- Are there other possible causes?

- What kinds of tests does my child need?

- What’s the best treatment?

- What are the alternatives to the primary approach that you’re suggesting?

- My child has these other mental or physical health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Are there any restrictions that my child needs to follow?

- Should I take my child to see other specialists?

- Is there a generic alternative to the medicine you’re prescribing for my child?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you recommend?

- Are there social services or support groups available to parents in my situation?

What to expect from your doctor

Your child’s doctor or mental health provider is likely to ask you a number of questions. Be ready to answer them to reserve time to go over any points you want to spend more time on.

Some questions the doctor may ask include:

- When did you first notice problems with your child’s behavior or emotional responses?

- Have your child’s behavioral or emotional issues been continuous or occasional?

- How are your child’s behavioral or emotional issues interfering with his or her ability to function or interact with others?

- Can you describe your child’s and the family’s home and living situation since birth?

- Can you describe interactions with your child, both positive and negative?

| RadKid.Org Directory: Reactive Attachment Disorder Sites |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Happy Digital Citizenship Week!

Here are some ideas from Janie Islas, PVUSD Technology Coach, on how to celebrate the week and talk with your kiddos about digital citizenship:

Elementary:

Follow the Digital Trail (lesson and video)

Brain Pop: Internet Safety (video)

Brain Pop: Information Privacy (video)

Tower of Treasure: Secure Your Secrets (game)

What Should You Accept? (video)

Secondary:

Digital Footprint (video)

Cyberbullying: Be Upstanding (lesson and video)

Perspectives on Chatting Safely Online (lesson and video)

Be Internet Awesome- Reality River: Don’t Fall For Fake (game)

Be Internet Awesome- Mindful Mountain: Share with Care (game)

If you would like to choose your own digital citizenship lesson, you can find a lot of videos on Brain Pop, you can search by grade level on our district Internet Safety page, or you can explore the following sites:

Parenting Classes Through “Triple P”

TRIPLE P IN A NUTSHELL

The Triple P – Positive Parenting Program ® is a parenting and family support system designed to prevent – as well as treat – behavioral and emotional problems in children and teenagers. It aims to prevent problems in the family, school, and community before they arise and to create family environments that encourage children to realize their potential.

Triple P draws on social learning, cognitive behavioral and developmental theory as well as research into risk factors associated with the development of social and behavioral problems in children. It aims to equip parents with the skills and confidence they need to be self-sufficient and to be able to manage family issues without ongoing support.

And while it is almost universally successful in improving behavioral problems, more than half of Triple P’s 17 parenting strategies focus on developing positive relationships, attitudes, and conduct.

Triple P is delivered to parents of children up to 12 years, with Teen Triple P for parents of 12 to 16-year-olds. There are also specialist programs – for parents of children with a disability (Stepping Stones), for parents going through separation or divorce (Family Transitions), for parents of children who are overweight (Lifestyle) and for Indigenous parents (Indigenous). Other specialist programs are being trialed or are in development.

BENEFITS OF TRIPLE P

Triple P is unlike any other parenting program in the world, with benefits both clinical and practical.

Flexible delivery

Triple P’s flexibility sets it apart from many other parenting interventions. Triple P has flexibility in:

Age range and special circumstance

Triple P can cater to an entire population — for children from birth to 16 years. There are also specialist programs – including programs for parents of children with a disability; parents of children with health or weight concerns; parents going through divorce or separation; and for Indigenous families.

Intensity of program

Triple P’s distinctive multi-level system is the only one of its kind, offering a suite of programs of increasing intensity, each catering to a different level of family need or dysfunction, from “light-touch” parenting help to highly targeted interventions for at-risk families.

How it’s delivered

Just as the type of programs within the Triple P system differ, so do the settings in which the programs are delivered – personal consultations, group courses, larger public seminars and online and other self-help interventions are all available.

Who can be trained to deliver

Practitioners come from a wide range of professions and disciplines and include family support workers, doctors, nurses, psychologists, counselors, teachers, teacher’s aides, police officers, social workers, child safety officers and clergy.

Evidence based

Triple P is the most extensively researched parenting program in the world. Developed by clinical psychologist Professor Matt Sanders and his colleagues at Australia’s University of Queensland, Triple P is backed by more than 35 years’ ongoing research, conducted by academic institutions in the U.S., the U.K., Canada, the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, Iran, Hong Kong, Japan, Turkey, New Zealand and Australia.

Population approach

Triple P has been designed as a population-based health approach to parenting, typically implemented by jurisdictions, government bodies or NGOs (non-government organizations) across regions or countries. The aim is to reach as many people as possible to have the greatest preventative impact on a community. The Triple P system can go to scale simply and cost efficiently. It has been shown to work with many different cultures and ethnicities.

Comprehensive resources

All Triple P interventions are supported with comprehensive, professionally produced resources for both practitioners and parents. The resources have all been clinically trialled and tested. The parent resources have been translated, variously, from English into 21 languages.

Organizational support

Triple P’s dissemination experts around the world have experience assisting all levels of government and non-government organizations and are available to advise through all stages of a Triple P rollout – from planning and training to delivery, evaluation and beyond. Triple P uses an Implementation Framework to help support the success and sustainability of Triple P.

Communications strategy

An integrated communications strategy, which helps destigmatize parenting support and reaches parents via a range of communications materials, puts parenting on the public agenda. It creates an awareness and acceptance of parenting support in general – and Triple P specifically.

Evaluation measures

The success of Triple P is easily monitored on both a personal level and across a population. Triple P provides tools for practitioners to measure “before” and “after” results with parents, allowing them to demonstrate Triple P’s effectiveness to the parents they work with and also to their own managers. computerized scoring applications can also be adapted to collate results across a region to show effects community-wide or within a target group.

Cost effective

Triple P’s system works to prevent overservicing and wastage, with its range of programs able to cater to the diversity of parents’ needs – from light-touch to intense intervention. It’s also a program that promotes self-regulation and self-sufficiency, as Triple P gives parents the skills they need to become problem solvers and confidently manage their issues independently, rather than rely on the ongoing support of a practitioner.

On a broader scale, as an early intervention strategy, Triple P has been shown to reduce costs associated with conduct disorder, child abuse and out-of-home placement, delivering significant benefits when compared to the cost of the program. Read more about Triple P’s cost efficiency.

LOCAL CONTACTS

If you represent an agency, organization, jurisdiction or government and would like to discuss implementing Triple P in your region, or inquire about training your staff to deliver Triple P to parents, please contact:

U.S.A.Triple P America Inc. |

AustraliaTriple P International Pty Ltd |

CanadaTriple P Parenting Canada Inc. |

GermanyTriple P Deutschland |

Latin AmericaTriple P Latin America |

New ZealandTriple P New Zealand Limited |

United KingdomTriple P UK Limited |

All other countriesTriple P International Pty Ltd |

Links

Triple P Online – Overview PDF

YouTube Triple P – Positive Parenting Program

Santa Cruz County Triple P Website

Promoting Disability Awareness on Campus

People with disabilities are not

their diagnoses or disabilities;

they are people, first.

Kathie Snow

Disability is Natural

Articles

Creating Positive School Experiences for Students with Disabilities By Amy Milsom

How to Talk to Kids About Disabilities

Tips for Talking to Your Child About Learning Disabilities

BULLYING AND DISABILITY: An Overview of the Research Literature by Fred Pampel, PhD

13 Tips on How to Talk to Children About Diversity and Difference

Changing How We Talk About Disabilities- GREAT Quick reference

Attitudes and Language – From Disability is Natural

Tools

Disability Awareness Activity Packet

Disability Lesson Plans from Learning to Give

Promoting Disability Awareness and Acceptance In Childhood By Anne Borys

How to Explain Disability to a Child

Content Provided by: United Cerebral Palsy of Greater Indiana

“Whether you’re explaining a disability to a child who has one or to a non-disabled child, the following key concepts should be kept in mind” advises Ava L. Siegler, Ph.D. in Child Magazine.

Compassion: Show a child you fully understand what a hurtful thing a disability can be.

Communication: Explain as much as you possibly can about the disability so a child does not become frightened by the unknown.

Comprehension: Make sure a child understands that the disability is never the child’s fault.

Competence: Convey the sense that even though a disability is very hard to deal with, a child with a disability will make progress and learn to do new things.

Suggested phrases to use when explaining a disability to a child:

Age of the Child When speaking to a child with a disability When speaking to a child without a disability 2 to 4 We don’t know why, but sometimes children are born without everything their bodies need, and that’s what happened to you. That means you’re going to have to work harder and we’re going to work hard to help you. Most children like you are born with everything they need, but sometimes children are born without everything they need. Sometimes they need crutches or wheelchairs or braces to help them do what you do naturally.” 5 to 8 “It’s really tough when your body can’t do everything you want it to do. It’s not fair that you have to work so hard to make your body do what you want. But everyone has some activities that are easy for them, and some that require more effort. You have this problem, but you’re lucky to have lots of talents, too.” “Kids are all different, and they have different strengths as well as things that are harder for them. Some things that are easy for you to do are very difficult for other children to do. It takes a lot of courage for kids with physical disabilities to keep trying and working at it.” 9 to 12 It’s a bad break for you to be born with a disability that makes things harder. But remember your abilities, too and work to strengthen them. It’s natural sometimes to feel angry but try not to give up. Whenever you see someone with a disability, remember that even though they are having a hard time, they’re still kids who need friends and understanding.

“Turn and Talks” in the Classroom Can Yield Many Positive Outcomes For Your Students

Procedures

Turn and Talk – Procedures and Routines

How to Use

1. Question

Pose a question or prompt for students to discuss and tell them how much time they will have. A one-to-two minute discussion is most productive.

2. Turn

Have students turn to a specific partner. Pair students using Eyeball Partners, Shoulder Partners, or Clock Partners (see variations below). Partner assignments should be set up beforehand so that students can quickly and easily pair up.

3. Talk

Set a timer for the allotted time, and have students begin discussing the assigned question or prompt. When time is up, ask partners to share out thoughts and ideas from their discussion.

When to Use

Use Turn and Talk at any time during a lesson to encourage accountable talk:

- As a warm-up activity to discuss previous lesson or homework assignment

- After five to seven minutes of oral or written input, to help student process what they have just heard or read

- During class discussions as a way for students to discuss ideas before sharing them with the class

- As a closing activity so that students can review what was learned in the lesson

- As a clarification tool for a complex problem or new guiding question posed by the teacher

Variations

Eyeball Partners

When students are seated at tables or in groups, “eyeball partners” are students who are facing in front of each other.

Shoulder Partners

When students are seated at tables or in groups, “shoulder partners” are students who are seated next to each other. This may also be done when students are seated in rows.

Clock Partners

Using a clock template, have students “make appointments” with four other classmates, one for 12 o’clock, one for 3 o’clock, one for 6 o’clock, and one for 9 o’clock. Partners may not be repeated. When ready to use partners, simply say “Work with your [choose one of the times] partner.” In Primary Grades PK-1, partners should be assigned by the teacher.

Articles

Turn and Talk: One Powerful Practice So Many Uses by Lucy West & Antonia Cameron

6 Easy Ways to Improve Turn & Talk for Student Language Development

Turn and Talk from HAMERAY PUBLISHING

Structured Student Talk From El Achieve

Turn and Talk Tips and Examples

Keep Your Students Engaged with “Turn and Talk” by RACHEL LYNETTE

TURN AND TALK PROMPTS

Please note that the list below is not meant to be a comprehensive list of Turn and Talk prompts, but simply a starter guide to get you thinking about how you can use this tool in your classroom.

READING

1. Which character did you identify most with in the book and why?

2. What do you predict will happen in the next chapter?

3. What did you visualize when you read this chapter?

4. Describe a connection you made while reading this piece. It can be a text-to-text, text-to-self, or text-to-world connection.

5. What is something the main character did that surprised you?

6. Choose a word that was unfamiliar to you when you first read this book. Explain to your partner how you determined the meaning of the word.

7. What do you think is the theme of the story?

8. Do you agree with the character’s actions? Why or why not?

9. After reading this book, what is one question you would want to ask the author?

10. What do you think the author’s purpose was for writing this story?MATH

1. Explain the strategy you used to solve this problem, and why you chose it.

2. Share three ways we use math in our everyday lives.

3. Analyze this problem and see if you can find the error the student made while solving it. Discuss with your partner how you would correct the error.

4. Do you agree or disagree with how I just solved this problem? Defend your answer.

5. What would be the next step?

6. Choose one math tool / manipulative we have used this year, and explain to your partner what it can be used for.

7. Which image / shape / pattern does not belong in this set of 4? Explain your thinking.

8. What information do you still need in order to solve this problem?

9. I can check my answer by……

10. I know my answer is reasonable because…

http://www.APLearning.comSCIENCE

1. The physical properties of ___________ and ____________ are similar because ___________________.

2. What do you predict will happen as we complete this investigation?

3. Choose one science safety tool and explain to your partner how to use it and why it is important.

4. Explain what you observed during the experiment, and why you think this happened.

5. Explain the process of how matter can change from one state to another.

6. Choose a plant or animal we have studied, and explain how it is adapted to thrive in its particular environment.

7. Take turns describing to each other the stages of the ___________’s life cycle.

8. A change we could make to our design is _______________. I think this will impact it by __________________.

9. Choose one environmental change, and explain to your partner how it impacts the environment.

10. How can we represent the data we have collected from this experiment?SOCIAL STUDIES

1. Which invention do you think had the greatest impact on our society and why?

2. Do you think it is important to learn about the history of our country? Defend your answer.

3. Think about the two cultures we have studied. Describe one way in which they are similar and one way in which they are different.

4. Describe how ________________ had an impact on society.

5. How can you determine if an online resource is valid?

6. Choose an important feature of a map or globe and explain its significance.

7. Explain how supply and demand effect the price of a good or service.

8. Find an example of one non-fiction text feature in your history textbook, show it to your partner, and explain how it helps you as a reader.

9. What do you think is the most important reason for a group of people to immigrate to another country?

10. Of the 10 amendments in the Bill of Rights, which do you think is most important? Defend your answer.

Anchor Charts

Building a Relationship with Students to Increase Learning in the Classroom

Articles

5 Tips for Better Relationships With Your Students – NEA

Featured article: Unconditional Positive Regard and Effective School Discipline By Dr. Eric Rossen

The Teacher as Warm Demander by Elizabeth Bondy and Dorene D. Ross

Educator’s Guide to Preventing and Solving Discipline Problems by Mark Boynton and Christine Boynton

The Power of Positive Regard by Jeffrey Benson

Building Positive Teacher-Child Relationships– CSEFEL

Unconditional Positive Regard

Carl Rogers described unconditional positive regard (UPR) as love and acceptance that are not dependent upon any particular behaviors. He often used the term “prizing” as shorthand for this feature of a relationship. According to Rogers, prizing is particularly important in the parent-child relationship.

Unconditional Positive Regard

Carl Rogers described unconditional positive regard (UPR) as love and acceptance that are not dependent upon any particular behaviors. He often used the term “prizing” as shorthand for this feature of a relationship. According to Rogers, prizing is particularly important in the parent-child relationship. Rogers argued that children who are prized by their parents experience a greater sense of congruence, have a better chance to self-actualize, and have are more likely to become fully functioning people than those whose parents raise them under “conditions of worth.”

Unconditional positive regard is also a crucial component of Rogers’ approach to psychotherapy. In fact, along with empathy and genuineness, Rogers asserted that UPR was one of the necessary and sufficient elements for positive psychotherapeutic change. When Rogers described UPR as “necessary,” he communicated that an unconditionally accepting and warm relationship between therapist and client is a prerequisite for therapy to be effective. This assertion is not particularly shocking; most individuals seeing a therapist would probably expect the therapist to have this type of nonjudgmental attitude, and would also probably expect therapy to progress poorly if the therapist was in fact judgmental or conditionally disapproving. When Rogers described UPR as “sufficient,” however, he made a bolder statement. The term “sufficient” suggests that if a therapist provides UPR, along with empathy and genuineness, to a client, the client will improve. No additional techniques or strategies are needed. The therapist need not analyze any dreams, change any thought patterns, punish or reward any behaviors, or offer any interpretations. Instead, in the context of this humanistic therapy relationship, the client will heal himself or herself by growing in a self-actualizing direction, thereby achieving greater congruence. This “necessary and sufficient” claim holds true, according to Rogers, regardless of the diagnosis or severity of the client’s problem.

In addition to the parent-child and therapist-client relationship, Rogers also considered the value of UPR in other relationships and situations. For example, he spent significant time and energy discussing the role that UPR might play in education, and in the teacher-student relationship in particular. Rogers criticized the mainstream American educational system as overly conditional. He believed that educators too often used the threat of poor grades to motivate students, and that students felt prized only when they performed up to educators’ standards (as measured by grades on exams, papers, etc.). He further believed that students may emerge from school having learned some essential academic skills, but also having learned that they are not trustworthy, that they lack internal motivation toward learning, and that only the aspects of themselves that meet particular academic criteria are worthy.

Rogers strongly recommended that teachers and administrators take a more humanistic and less conditional approach to education. He argued that UPR in schools would communicate to children that they are worthy no matter what; as a result, their sense of congruence and their tendency toward self-actualization would remain intact. Students, according to Rogers, should be trusted to a greater extent to follow their own interests and set to their own academic goals. Rather than threatening students to study for exams and write papers in which they have little interest, prize them wholly and allow them greater freedom to choose that which they want to pursue. Advocates of Rogers’ humanistic approach to education argue that it would enhance students’ self-worth, which in turn may preclude many of the psychological and social problems that children encounter. Critics of Rogers’ humanistic approach to education argue that without conditions of worth based on academic achievement, students would have no provocation to learn, and would demonstrate lethargy rather than self-motivation.

Andrew M. Pomerantz, Ph. D.

Preparing for Halloween with Children on the Autism Spectrum

4 Steps to Prepare Your Child with Autism for Halloween

By – We Rock the Spectrum Kid’s Gym in Tarzana, CA

Halloween is a family-friendly holiday that’s especially exciting for younger children. It’s a time once a year where they can dress up in rockin’ costumes, stay out late, explore their neighborhood, and — most importantly — make childhood memories that will last them a lifetime. If your child has autism, there’s no reason he or she can’t participate in this special time as well! Children with autism are very capable, but often need more preparation than a neuro-typical child. That’s why we created a list of steps to help prepare your child with autism for Halloween festivities.

1) Visualize

Show Them Photos and Videos

As any parent knows, the best way to reduce the anxiety and nerves that come from the unknown is to help your child visualize what’s going to happen before it happens. On Halloween night, the neighborhood and world as your child knows it seemingly changes. Families will be roaming the streets wearing different costumes, running from door to door asking for candy. Show your child what it’s going to look like with photos and videos of previous Halloweens. YouTube is filled with videos of parents filming their children’s first trick-or-treating experience. Preview the videos to make sure they’re safe, but use these to show your child what it will be like. If you have your own home videos of the night, that’s all the better!

Preview the Route

Take your child on a walk around the neighborhood to get used to it. If you have a specific route planned out for the night, walk them through it and let them know what houses they’ll be going to, and which ones they won’t. Have them examine the Halloween decorations to make sure they aren’t surprised or scared the night of.

2) Explain

Talk Them Through the Social Cues

After you’ve shown your child what’s going to happen on Halloween, make sure you explain it as well. Talk them through the actions they’ll take, especially the social cues they’re expected to do. Explain how to knock on doors, ask for candy, and help them come up with good replies for when someone asks them a question about their costume or candy preference.

Research to Answer Any Questions

Kids are curious! Be sure to do a little research of your own so that when your child begins asking you a thousand questions about Halloween — how it started, why you say “Trick-or-Treat”, what’s with the costumes, etc. — so that you can provide not only the answers, but the assurance that all is going to be okay.

3) Practice

Dress Them in Their Costumes Before

After you’ve found the costume that your child wants (a process that deserves a step-by-step guide itself!), don’t wait until show time to practice putting it on. Children with Autism, especially children with Sensory-Processing Disorder, are very particular about their clothing choices and comfort. If your child has a particular outfit they are most comfortable wearing, consider reducing stress by complimenting the outfit with a cape or mask so they can still have the comfort of their favorite clothes. If your child is willing to try a costume, then plan on having them wear it a few times before Halloween until they can put it on relatively stress-free.

Walk Them Through a Test-Run

Before the big day, take everything you’ve been working on and put it into practice. Have them get into their costumes, go over their social cues with you along with any last questions they have, and then take them on their Halloween route! If you can, even talk with neighbors who would be willing to participate in this practice with you. Have your child knock on you neighbors door and go through the motions of trick-or-treating, but without the actual tricks or treats (save the excitement for the actual day as a reward!).

4) Perform

Finally, the big day is here! It’s Halloween and it’s time to get your child dressed up and ready to explore the neighborhood with other children and friends. Keep in mind that any success, no matter how small, is still a success and a step in the right direction. Maybe your child only makes it to three houses — but that doesn’t mean they won’t make it to three more next year! Be positive and happy for any progress you can make, and remember that this holiday is supposed to be about family fun and good memories, so be sure to know your child’s limits and compromise if you must. It will only ensure a happier time for the both of you.

Articles

Halloween for children with Autism by Bethany Sciortino

Trick Or Treat! By Lisa Ackerman

Tips for Preparing Your Child with Autism for Halloween

Halloween Tips for Parents with Children on the Autism Spectrum May Institute

Social Stories

16 Printable Halloween Social Stories

- What to expect on Halloween by Positively Autism

- Halloween Tips & Social Story by Therapics

- Halloween Social Story by Indiana Institute on Disability and Community

- Halloween Party by Teachers Pay Teachers

- Halloween Party 2 by Teachers PayTeachers

- Carving a Pumpkin by SETBC

- Trick or Treat, Wearing a Costume by Creating and Teaching

- Trick or TreatCards by Teachers Pay Teachers

- Trick or Treat 1 by TeachersPay Teachers

- Trick or Treat 2 by Teachers PayTeachers

- Trick or Treat 3 by Project Autism

- Trick or Treat 4 by Teachers Notebook

- Trick or Treat 5 by Chit Chat andSmall Talk

- Trick or Treat 6 by CCSD

- Trick or Treat 7 by A Legion for Liam

- Trick or Treat 8 by Autism Tank

- Halloween- Icons and Text by Indiana University

- What to Expect on Halloween Social Skill Story by positively autism

- PPT Learning About Halloween by Carol Gray

- See Example below.

Halloween Social Story

My name is _____________________. Soon it will be Halloween. Lots of people like to dress up in costumes for Halloween. They dress up because it is fun. When kids wear costumes they are still the same kid inside the costume. The costume may look different but really the kid wearing the costume is the same. There are many costumes that are soft and feel good to wear. I can wear a costume, too! I may wear a ________________ costume.

On Halloween, different kids like to do different things. Some kids like to go to a party. Some kids like to go trick-or-treating. On Halloween I want

to_____________________________________________.Halloween is exciting so sometimes there can be too much excitement. When I feel too excited

I can take a break or _____________________________________________________.It is important to stay safe on Halloween. Kids need to stay with an adult. Kids need to always stay on the sidewalk and wait until an adult can take them across the street. I will only go to houses where the light is on and the house looks friendly.

I may get lots of treats on Halloween. My ________________ will let me know when I can eat my treat.

I will have fun on Halloween!

Trick or Treat Cards

Link to other styles of cards: Click Here

Link to Printable PDF of above cards for nonverbal/ reluctant to say “Trick or Treat”.

Suicide Prevention Training via ASIST

Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST) is a two-day interactive workshop in suicide first aid. ASIST teaches participants to recognize when someone may have thoughts of suicide and work with them to create a plan that will support their immediate safety. Although ASIST is widely used by healthcare providers, participants don’t need any formal training to attend the workshop—anyone 16 or older can learn and use the ASIST model.

Since its development in 1983, ASIST has received regular updates to reflect improvements in knowledge and practice, and over 1,000,000 people have taken the workshop. Studies show that the ASIST method helps reduce suicidal feelings in those at risk and is a cost-effective way to help address the problem of suicide.

Learning goals and objectives

Over the course of their two-day workshop, ASIST participants learn to:

- Understand the ways that personal and societal attitudes affect views on suicide and interventions

- Provide guidance and suicide first aid to a person at risk in ways that meet their individual safety needs

- Identify the key elements of an effective suicide safety plan and the actions required to implement it

- Appreciate the value of improving and integrating suicide prevention resources in the community at large

- Recognize other important aspects of suicide prevention including life-promotion and self-care

Workshop features:

- Presentations and guidance from two LivingWorks registered trainers

- A scientifically proven intervention model

- Powerful audiovisual learning aids

- Group discussions

- Skills practice and development

- A balance of challenge and safety

Suicide is a Wicked Problem

Suicide is a wicked problem because it kills and injures millions of people each year, it is a complex behavior with many contributing factors, and it can be difficult to prevent. 1.1 One million people die by suicide each year An estimated one million people died by suicide in 2000; over 100,000 of those who died were adolescents (World Health Organization, 2009). If current trends continue, over 1.5 million people are expected to die by suicide in the year 2020 (Bertolote & Fleischmann, 2002). The world wide suicide rate is estimated to be 16 deaths per 100,000 people per year (World Health Organization, 2009).

For every person who dies by suicide, many more make an attempt

The ratio of suicide attempts to deaths can vary depending upon age. For adolescents, there can be as many as 200 attempts for every suicide death, but for seniors there may be as few as 4 attempts for every suicide death (Berman, Jobes, & Silverman, 2006; Goldsmith, Pellmar, Kleinman, & Bunney, 2002). A recent household survey conducted in the United States estimated that 8.3 million adults had serious thoughts about suicide in the past year, that 2.3 million had made a suicide plan, and 1.1 million had attempted suicide (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies, 2009). A survey of Australian adults conducted by the World Health Organization found that 4.2% of respondents had attempted suicide at least once during their lifetime (De Leo, Cerin, Spathonis, & Burgis, 2005).

The devastation of suicide affects many

Suicide is devastating. Not only for those who suffer, are injured, and die from it, but also for their family, friends, and others. The total devastation of suicide is perhaps best summarized by a quote from Kay Redfield Jamison:

Suicide is a particularly awful way to die: the mental suffering leading up to it is usually prolonged, intense, and unpalliated. There is no morphine equivalent to ease the acute pain, and death not uncommonly is violent and grisly. The suffering of the suicidal is private and inexpressible, leaving family members, friends, and colleagues to deal with an almost unfathomable kind of loss, as well as guilt. Suicide carries in its aftermath a level of confusion and devastation that is, for the most part, beyond description (Jamison, 1999, p. 24).

Additional Reading

- ASIST info sheet (PDF / 3.9 MB)

- ASIST and the NAASP clinical workforce guidelines (PDF / 257 KB)

- Evidence in Support of the ASIST 11 Program (PDF / 172 KB)

- ASIST Experiences and Recommendations (PDF / 989 KB)

- Review of ASIST (PDF / 1.8 MB)

- The Use and Impact of ASIST in Scotland (PDF / 1.5 MB)

- Gould Study Summary (PDF / 1.9 MB)

- Review of the Operation Life Suicide Awareness Workshops (PDF / 2.4 MB)

- Evaluation of the Scottish safeTALK pilot (PDF / 351 KB)

- safeTALK Manitoba Evaluation Highlights Report (PDF / 122 KB)

- SafeTALK Manitoba Evaluation Full Report (PDF / 1.5 MB)