Recently, my little girl started in a home daycare. Initially, she struggled with separation anxiety. She has since settled down (whew!). This post has some good pointers on Separation Anxiety.

How parents can help children at home

There are things parents can do to help children and adolescents learn to manage their anxious feelings. Parent support plays a key role in helping kids learn to cope independently. Try these strategies at home to help your child succeed outside of the home:

-Make a plan to help your child transition to school in the morning (arrive early, act as the teacher’s helper before the other kids arrive, get some exercise on the playground before the bell rings)

-Help your child reframe anxious thoughts by coming up with a list of positive thoughts (it even helps to write these on cards and put them in the backpack)

-Write daily lunchbox notes that include positive phrases

-Avoid overscheduling. Focus on playtime, downtime, and healthy sleep habits

-Alert your child to changes in routine ahead of time

-Empathize with your child and comment on progress made

– Teach relaxation strategies

Kids need to learn a variety of tools to use when feeling anxious and overwhelmed. It’s nearly impossible to use adaptive coping strategies when you’re dealing with intense physical symptoms of anxiety, so the first step is with work on learning to calm the anxious response.

- Deep breathing is the best way to calm rapid heart rate, shallow breathing and feeling dizzy. Teach your child to visualize blowing up a balloon while engaging the diaphragm in deep breathing. Count your child out to help slow the breathing (4 in, 4 hold, 4 out).

- Guided imagery: Your child can take a relaxing adventure in her mind while engaging in deep breathing. Tell a quick story in a low and even voice to help your child find her center.

- Progressive muscle relaxation: Anxious kids tend to tense their muscles when they’re under stress. Teach your child to relax her muscles and release tension beginning with her hands and arms. Make a fist and hold it tight for five seconds, then slowly release. Move on to the arms, neck and shoulders, and feet and legs.

– Teach cognitive reframing

Kids with social anxiety disorder are often overwhelmed by negative beliefs that reinforce their anxious thoughts. Their beliefs tend to fall into the following categories:

- Assuming the worst case scenario

- Believing that others see them through a negative lens

- Overreacting

- Personalizing

Teach your child to recognize negative thoughts and replace them with positive ones. If your child tends to say things like, “My teacher thinks I’m stupid because I’m bad at reading,” help him recognize the negative thought, ground it in reality (a teacher’s job is to help kids learn not judge them on what they already know), and replace it with a positive thought (“I’m having a hard time reading but my teacher will help me get better.”)

– Teach problem-solving skills

Children with social anxiety disorders tend to become masters of avoidance. They do what they can to avoid engaging in situations that cause the most anxiety. While this might seem like the path of least resistance, it can actually make the social anxiety worse over time.

Teach your child to work through feelings of fear and anxiety by developing problem-solving skills. If a child fears public speaking, for example, she can learn to practice several times at home in front of a mirror, have someone videotape her and watch it back, find the friendly face in the room and make eye contact, and use deep breathing to calm anxious feelings.

Help your child identify her triggers and brainstorm potential problem-solving strategies to work through those triggers.

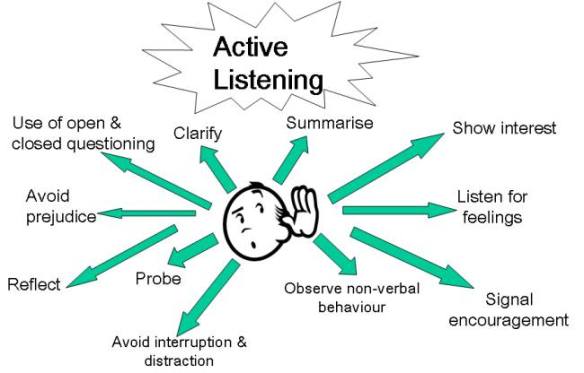

– Work on friendship skills

While you can’t make friends for your child, you can help your child practice friendship skills. Practice these skills using role play and modeling to help your child feel at ease with peers:

- Greetings

- Sliding in and out of groups

- Conversation starters

- Listening and responding

- Asking follow up questions/making follow up statements

Books

What to Do When You Worry Too Much: A Kid’s Guide to Overcoming Anxiety (What to Do Guides for Kids) by Dawn Huebner

The Kissing Hand by Audrey Penn

Wemberly Worried by Kevin Henkes

First Day Jitters by Julie Danneberg

Llama Llama Misses Mama by Anna Dewdney

Love You All Day Long by Francesca Rusackas

When I Miss You by Cornelia Spelman

If things progress-

How to get help for your child

The best treatment to help children struggling with school refusal includes a team approach. While children tend to focus on what they don’t like or worry about at school, the truth is that the underlying issues can include stress at home, social stress, and medical issues (a child who struggles with asthma, for example, might experience excessive worry about having an asthma attack at school). It helps to have a strong team that includes the classroom teacher, family, a school psychologist (if available), and any specialist working with the child outside of school.

- Assess: The first step is a comprehensive medical and psychological evaluation. Given that school refusal is generally related to an underlying anxiety or depressive disorder, it’s important to get to the root of the problem and begin there. This will likely include both family and teacher questionnaires or interviews.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: This highly structured form of therapy helps children identify their maladaptive thought patterns and learn adaptive replacement behaviors. Children learn to confront and work through their fears.

- Systemic desensitization: Some children struggling with school refusal need a graded approach to returning to school. They might return for a small increment of time and gradually build upon it.

- Relaxation training: This is essential for children struggling with anxiety. Deep breathing, guided imagery, and mindfulness are all relaxation strategies that kids can practice at home and utilize in school.

- Re-entry plan: The treatment team creates a plan to help the student re-enter the classroom. Younger children might benefit from arriving early and helping the teacher in the classroom or helping at the front desk. The plan also includes contingencies to help the student during anxious moments throughout the day (i.e., using fidget toys, taking a brain break to color, a walk outside with a teacher’s aide, etc.)

- Routine and structure: Anxious children benefit from predictable home routines. Avoid over-scheduling, as this can increase stress for anxious kids, and put specific morning and evening routines in place.

- Sleep: Sleep deprivation exacerbates symptoms of anxiety and depression. It also makes it difficult to get up and out to school in the morning. Establish healthy sleep habits and keep a regular sleep cycle, even during holidays and on the weekends.

- Peer buddy: Consider requesting a peer buddy for recess, lunch, and other less structured periods as anxiety can spike during these times.

- Social skills training: Many students who struggle with making and keeping friends feel overwhelmed in the school environment. Social skills groups can help kids learn to relate to their peers and feel comfortable in larger groups.

There isn’t a quick fix for school refusal. You might see periods of growth only to experience significant setbacks following school vacations or multiple absences due to physical illness. Acknowledge your child’s difficulty, engage in open and honest communication about it, empathize with your child, and pile on the unconditional love and support.

References

https://www.psycom.net/social-anxiety-how-to-help-kids

http://www.educationandbehavior.com/strategies-schools-help-children-separation-anxiety/

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/worry-free-kids/201710/how-help-child-overcome-school-refusal